The 1980s

The following text was excerpted from a personal history written by Erik W. Austin, whose career at ICPSR lasted 41 years and included service as interim executive director. Austin says: “I have written these pages from my recall of events and developments described below. These recollections are my own, and do not reflect ‘official’ institutional history. Admittedly, some aspects of the Consortium’s programs and activities will be slighted due to my tangential involvement in them. Contemporary survey data developments, the details of computational matters, and the Summer Program are three such areas that won’t get as much ink as they undoubtedly deserve.”

The following text was excerpted from a personal history written by Erik W. Austin, whose career at ICPSR lasted 41 years and included service as interim executive director. Austin says: “I have written these pages from my recall of events and developments described below. These recollections are my own, and do not reflect ‘official’ institutional history. Admittedly, some aspects of the Consortium’s programs and activities will be slighted due to my tangential involvement in them. Contemporary survey data developments, the details of computational matters, and the Summer Program are three such areas that won’t get as much ink as they undoubtedly deserve.”

The 1980s began badly for the social sciences. The ascension to the US presidency of conservative icon Ronald Reagan ushered in a concerted attack on the social science enterprise by Executive Office appointees and (to a lesser degree) the US Congress. The Administration’s goal to “de-fund” the social sciences was ultimately thwarted after several years of strenuous effort on the part of social scientists and their friends in Congressional offices. Then-ISR Director Thomas Juster recalls traveling to Washington, DC, on nearly a biweekly basis to speak to officials about the societal benefits of the type of social science research that ISR was known for. Funding for social research did, however, become harder to get for the average social scientist. Some of the landmark continuing social science studies (GSS, PSID, ANES) were able to retain ongoing funding, but single-investigator research studies were difficult to get funded.

ICPSR officials worried that the straitened economic conditions would impact ICPSR membership. The opposite happened, though — membership increased during the ’80s. Explanations for the growth ranged from greater staff effort to recruit and retain institutional members, to a heightened value put on secondary analysis when funding for new data collection became harder to obtain. An additional factor was the decision to “hold the line” on membership dues, foregoing any increase in those institutional dues for a number of years. This allowed many institutions to remain in the membership in spite of economic hardship, as well as permitting addition to the membership of a large number of universities outside academe’s “top tier.” More affordable dues, therefore, was a factor in shifting the organization away from an elitist orientation.

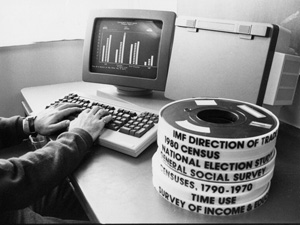

Technological change characterized the 1980s for ICPSR in ways not seen theretofore. The Consortium participated fully in the trend away from mainframe academic computing with the acquisition of a PR1ME “mini-computer” funded largely by the National Science Foundation. Communicating computer terminals replaced the punch card technology, and were followed by the early desktop computers by the late-1980s. Research data collections would continue to be processed by archival staff on both mainframe and minicomputers, and data requested were still exported to member campuses on magnetic tape, usually accompanied by paper codebooks.

At the beginning of the 1970s, ICPR played almost no role in distributing microdata from the US Census Bureau. (The Bureau provided very little public use microdata until 1970; scanty collections of tract-level aggregate data from the 1960 decennial Census had been prepared, along with a rudimentary Public Use Sample from that Census.) These were distributed by the Census Bureau’s newly-formed Data Access and Use Laboratory (DAULabs), and became quite popular with academic researchers and local governments. Census Bureau employee John Beresford headed DAULabs at the time and could see the potential of widespread distribution of microdata that researchers could recombine and reaggregate to suit their demographic investigations. (Up to that point, the Census Bureau believed that they WERE releasing their data, in the form of their extensive series of published reports, replete with detailed statistical tables that “answered all the questions that anybody could possibly have.”) Before the 1970 Census was conducted, Beresford left the Bureau and formed a private company, the Data Use and Access Laboratories (DUALabs), Inc. He sold discounted subscriptions to the individual-level and aggregate data files that the Bureau was selling for quite high prices; compressed the data files so that they would fit on fewer reels of magnetic tape (the preferred distribution medium of the day); and distributed software that decompressed his version of the data files and produced tabular reports from the decompressed files. Many universities bought subscriptions to the DUALabs files and software. (ICPSR was prohibited from doing so by the quite understandable DUALabs policy of non-redissemination.) By the time the 1980 Census rolled around, DUALabs was tottering, its software (based on PL-1 code) was shaky, and the prices it charged had become unaffordable. Many ORs pleaded with ICPSR to become a “buyers’ cooperative” and acquire the 1980 Census for redistribution to member institutions at vastly reduced prices.

The Consortium did that, acquiring virtually all of the 1980 US Census data files and re-selling them to members for a fraction of the Census Bureau price. We also acquired almost all of the DUALabs-format 1970 Census files, although this turned out to be more problematic than valuable. Those files, no longer available from the Census Bureau, taught ICPSR a lesson that if important social science data files were to be preserved for future use, ICPSR would probably have to acquire and preserve them on its own hook.

The Consortium did that, acquiring virtually all of the 1980 US Census data files and re-selling them to members for a fraction of the Census Bureau price. We also acquired almost all of the DUALabs-format 1970 Census files, although this turned out to be more problematic than valuable. Those files, no longer available from the Census Bureau, taught ICPSR a lesson that if important social science data files were to be preserved for future use, ICPSR would probably have to acquire and preserve them on its own hook.

So, we determined to get into the 1980 Census data file distribution in a major way. The ICPSR community also had need for training in the nature of the files to be made available by the Census Bureau, their content, and means of using them for academic research. We tentatively scheduled a one-week workshop for the 1981 Summer Training Program. Who to teach it, though? Hardly anyone was familiar with the new format of the 1980 Summary Tape Files, as they were to be called, and only a little more familiar with the re-named 1980 Public Use Microdata Survey files (PUMS, a considerable improvement over the 1970 acronym of PUS). Jerry Clubb pulled me aside and said, “You can teach this workshop.” What?” I said. “I’m an historian. I’ve used historical U.S. Census data, the stuff we key-entered from publications, but nothing past 1960. I’m not a demographer, and I don’t know anything about the structure of these files.” “There’s technical documentation, isn’t there?” said Jerry. “Well, yes!,” I replied. “Then, you read the technical documentation carefully, and present it to the workshop participants. Just remember the old professorial injunction: stay at least one day ahead of the class.”

While that made me very nervous, I reluctantly agreed to “teach” the workshop. It was oversubscribed, and more than 25 beaming faces greeted me on the first day of the workshop. We had acquired some of the Summary Files, and installed Census-Bureau-supplied software for manipulating them (called CENSPAC,i ICPSR still offers it as a downloadable product!!) I held my own for the first day or so, until some hard questions came up. Mercifully, I had an ally: one of the participants in the workshop was eminent demographer Clifford Clogg. The rest of the week went as follows: hard (but fair) question, Austin taking a shot at the answer, and then turning to Clogg and saying “Does that sound right to you, Cliff?” Naturally, he bailed me out time and again. Subsequently, we brought in professionals (from the Bureau and from the demography community) to do the instructing of how to use decennial census data files, including such iconic Census Bureau staffers as Marshall Turner, Tim Jones, Larry Carbaugh, John Kavaliunis, and former Bureau Director Barbara Everitt Bryant.

In 1985, ICPSR made two of the best hires in its history. Signing on in that year as a Data Archive Specialist was Peter Granda, holder of a U-M PhD in the medieval history of India, but with little prior training or experience in the social sciences. He apprenticed in the General Archive on two large data conversion projects (the 1935-1937 Cost of Living Survey, and the State Legislative Election Returns collected for 1968-1990), took statistics and methods classes in the Summer Training Program, and became one of the Consortium’s most skilled data processors. He advanced through a series of Research Associate titles, and was chosen as Assistant Director of Archival Development in 1993. Through his work on the National Survey of Family Growth, he became ICPSR’s most knowledgeable and skilled expert in modern survey data collection methods and technology, and garnered across ISR a reputation for excellence in all phases of the social science research data enterprise. In 2006, Peter was appointed a full-fledged Archivist at U-M, and was named Acting Director of Collection Development at ICPSR. His contributions (for over 20 years at the time of this writing) have been signal, and will only expand in coming years. [Ed. Granda became associate director of ICPSR in October 2013, and he remains director of the General Archive and the Health Care and Medical Archive.]

Mary Vardigan also joined the staff in 1985. She began as an Editorial Assistant, and progressed through Assistant, Associate, and full Editor ranks, parlaying her two degrees in English language and literature and her superb writing ability into mastery and substantial improvement of all of ICPSR’s print publications. By the mid-1990s, as print publications at ICPSR (and elsewhere) were superseded by digital publishing on the Web, Mary took charge of the Consortium’s Internet face on the world.

No one has been more important than Mary in pushing ICPSR’s organizational and collection-related metadata to the highest modern standards of clarity and informativeness. She has led ICPSR’s efforts (in cooperation with two dozen other social science organizations worldwide) to develop an international XML-based standard for social science metadata, known as the Data Documentation Initiative (DDI). In 2004 she was named Director of ICPSR’s new department of Collection Delivery and an Assistant Director of ICPSR. Her service on the ISR Policy Committee (2004-2006) contributed to her burgeoning reputation across ISR for innovation, collegiality, and competence. Mary remains ICPSR’s best pure writer; staff preparing documents intended for external audiences have learned to route them through Mary for her thorough editorial review and language improvement. Her advanced professionalism and skill have been crucial to ICPSR’s well-earned reputation as the worldwide standard-setter for social science information presentation, display, and retrieval.

Consortium staff paid more attention to the international scene in the 1980s. Executive Director Jerry Clubb took part in numerous research exchange visits with scholars from the Soviet Union, traveling to Moscow a handful of times, and entertaining dozens of Soviet historians and other social scientists in Ann Arbor. Some small number of datasets was exchanged between ICPSR and groups of Soviet scholars, but those scholars’ lack of hard-cash resources effectively prevented the establishment of ICPSR memberships by any of the Russian or Eastern European universities and research institutes.

Jerry nevertheless put high value on continuing the contacts with Soviet scholars, and they too valued the contacts as a means of keeping open a window on the world outside the USSR. On more than one occasion in the 1980s, when saber-rattling from the Reagan or Brezhnev/Andropov/Chernenko administrations dominated the news, Jerry received pleas from Soviet scholars to keep the lines of communication open. None of the parties was too hopeful, though, about any serious regime change in the USSR, and they were as surprised as the rest of the world by the cataclysmic changes after 1989.

The international role of the Consortium was extremely important for the development of empirical social science throughout the world, through its system of national memberships and the Summer Training Program, which attracted hundreds of students and scholars from over seven dozen nations. These efforts helped build a genuinely international social science community, and fostered the development of truly comparative social science.

Early in the decade, ICPSR was approached by PhD-trained social scientists working for the US Central Intelligence Agency, requesting a membership in ICPSR. These scientists were heavy users of empirical data and collected sizeable bodies of quantitative social science data, as well. Jerry and the Council pondered this long and hard but finally let the request expire without action. Several of our European members convincingly argued that their continuing affiliation with ICPSR would be imperiled if the CIA became a regular member of ICPSR, due to political sensitivity in their countries towards the US intelligence establishment.

In 1980, ICPSR began a relationship with a sponsoring organization that has lasted more than a quarter-century. This was with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), the largest health and medical care philanthropy in the US. A vice president of RWJF approached Jerry Clubb with a request for assistance in obtaining from a Foundation grantee a data collection on physicians’ practice patterns. ICPSR was offered a small grant to acquire, process, and archive a set of data files produced from this study. I questioned the wisdom of becoming engaged in this activity, as I could think of very few secondary analysts who looked to ICPSR for data who would be interested in conducting research on data of this sort. Jerry replied, “Let’s do it anyway. You never know — this could turn into a long-term funding opportunity for ICPSR.” Prophetic words, indeed.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, I wrote a series of grant proposals to RWJF that funded the archiving of nearly a hundred data collections on health and health care in the US, culminating in the late-1990s with the establishment of the Health and Medical Care topical archive (HMCA). A number of these data collections were popular with secondary analysts, and were quite heavily used. The affiliation with RWJF became the third-longest continuous affiliation with a sponsor in ICPSR’s history. A series of project officers at RWJF have shepherded our grant proposals through the Foundation, assuring each time that we were awarded the full amount of funds we asked for. (Our relationship with RWJF has been so cordial that our then-project officer felt comfortable calling me in the early 1990s for help with a problem the Foundation was facing. Seems they hadn’t been giving enough money away, and solicited from me ideas for a grant they could fund ASAP. I readily agreed to “help them out,” hurriedly put together a proposal for a one-week training workshop associated with the ICPSR Summer Training Program, and sent it to the Foundation. It was funded within a month.)

Two additional Associate Directors were appointed by Jerry Clubb in the early 1980s, both of them from outside CPS and the University of Michigan. Hubert M. (Tad) Blalock from the University of Washington’s Sociology Department joined the masthead in 1981. He was followed in 1983 by Norval Glenn, a sociologist at the University of Texas. Both had been members of the ICPSR Council, and they remained active and attentive to ICPSR affairs for well over a decade as Associate Directors. Their presence signaled strongly that ICPSR was pan-disciplinary and operated for and with the assistance of scholars from universities all over the country.

In the 1980s, I held a University title of Senior Research Associate and an ICPSR title as Director of Archival Development. I helped recruit topical archive managers in the fields of aging and criminal justice, after Mike Traugott stepped down from those roles and left ICPSR to concentrate on more standard academic pursuits. With Carolyn Geda, I also lectured on digital archiving in the U-M School of Information and Library Science from 1983-1986. During the 1980s, I published three books and a half-dozen articles on historical and digital archiving themes, often in collaboration with colleagues at ICPSR and other universities. On the surface, my professional life and the fortunes of the Consortium seemed to be going quite smoothly as the end of the decade of the ’80s approached. Yet some ripples had begun to appear that presaged turbulence downstream.

“The Troubles”

Organizational tensions within CPS increased in the early 1980s as ICPSR grew in size, membership, and revenues. The departure of Warren Miller (founder of both ICPSR and CPS) in 1981 brought new leadership to CPS: Phil Converse served as CPS Director from 1982-1986, and was succeeded by Harold Jacobson (1986-1996). Converse had a long but somewhat arms-length association with ICPSR, in spite of his decade of service as an Associate Director of ICPSR. Jacobson had virtually no involvement with ICPSR until his appointment as CPS Director. (Jacobson had served as chair of U-M’s Political Science Department before being appointed as CPS Director.) Thus the leadership of CPS in the 1980s lacked the close connection to ICPSR that Warren Miller had had since the inception of the organization.

Throughout the decade, a dispute simmered between ICPSR and CPS over the control and allocation of indirect cost recovery funds and other money associated with membership dues, grants, and contracts. The perceived unfairness of the arrangement wherein ICPSR had to apply for access to these funds prompted Clubb and former Council members Heinz Eulau and Tad Blalock to petition for more control over resources they thought ICPSR had raised in the first place. Jacobson resisted any changes and claimed that CPS was actually subsidizing ICPSR.

No doubt, some other factors figured into the conflict that beecame more heated as the decade progressed. One was a clash of personalities between Clubb and Jacobson. The two also disagreed about the core mission and audience of ICPSR, the operation of the Summer Program, and the role of the ICPSR Council.

Eventually, the conflict resulted in the formation in 1988 of a review committee led by Blalock, the former ICPSR Council member from the University of Washington. Also appointed were four other former Council members: Judith Rowe (Princeton University), John Sprague (Washington University, St. Louis), Robert Holt (University of Minnesota), and Allan Bogue (University of Wisconsin). The group’s tasks were to review ICPSR’s activities, budgets, and staff performance. The committee requested documents from Consortium staff and CPS officials, interviewed numerous individuals in person or by phone and correspondence, and solicited evaluations from all current ICPSR Official Representatives as well as a number of social scientists. The review process took over a year.

Eventually, the conflict resulted in the formation in 1988 of a review committee led by Blalock, the former ICPSR Council member from the University of Washington. Also appointed were four other former Council members: Judith Rowe (Princeton University), John Sprague (Washington University, St. Louis), Robert Holt (University of Minnesota), and Allan Bogue (University of Wisconsin). The group’s tasks were to review ICPSR’s activities, budgets, and staff performance. The committee requested documents from Consortium staff and CPS officials, interviewed numerous individuals in person or by phone and correspondence, and solicited evaluations from all current ICPSR Official Representatives as well as a number of social scientists. The review process took over a year.

The review committee delivered its report (pdf) to Jacobson and Taeuber in June of 1989. In it, the committee reported that all areas of Consortium activity were functioning very well, particularly the data processing, order fulfillment, and the Summer Training Program. The committee explored the tensions and acrimony between ICPSR and CPS, and concluded that these were largely caused by a mismatch of interests and mission between the two organizations. The review committee’s two major recommendations were to remove ICPSR administratively from under the Center for Political Studies, and to rewrite the Memorandum of Organization to better specify the role of the ICPSR Council “in performing its stewardship for the interests of the member institutions.” The conclusions of the review report came as no surprise to ICPSR or its Council, but were hardly what CPS expected the review committee to find. Over the following two years (1989-1991), ISR, CPS, and the Council labored to fulfill the second of the review committee’s recommendations, producing in 1991 three documents that replaced the Memorandum of Organization: a Constitution, set of Bylaws, and a Memorandum of Agreement between the Consortium and ISR. The latter effectively kept ICPSR under administrative control of CPS. No action was taken on the recommendation to separate ICPSR from CPS for over eight years.ii

i Thanks go to longtime ICPSR staff member Peter M. Joftis for dredging up the name “CENSPAC” from the bowels of institutional memory. Peter’s career at ISR began in the early 1970s when, as a graduate student in Political Science, he worked on the American National Election Study. He transferred to ICPSR in the late-1970s to work in the Computer Support Group. He was Director of that group from 1985-1995.

ii In some respects, ICPSR throughout its history suffered somewhat from its anomalous status. It was located at the University of Michigan and was sometimes viewed as a “Michigan operation” exploiting other universities. That was the view of some at the University of Wisconsin — U-M’s chief rival — but it was a view held at other universities, as well. On the other hand, ICPSR could not be fully controlled by the University of Michigan, and hence people there were sometimes unwilling to take responsibility for its well-being. No doubt this viewpoint had an impact on implementation of the Blalock Review Committee’s recommendations.